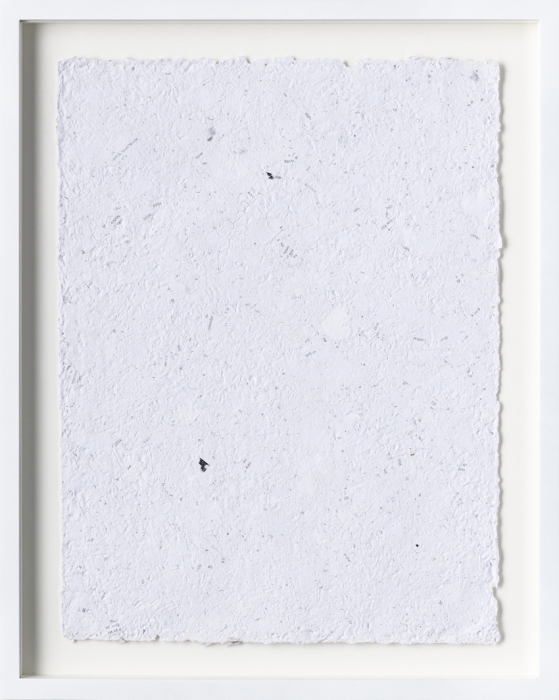

Painting with hydrochloric acid on nylon, 1961

There are lots of ways to paint, as a quick wander through any major art museum will amply demonstrate. But there are those who change out understanding of art through their work, and Gustav Metzger is one such. Metzger’s notion of auto-destructive art, which he initially defined in 1959, was an interesting and highly-influential on which was rooted in the belief that Western society was failing (Metzger has been a Marxist all his adult life). The idea is that the work has the capacity to destroy itself or that it is destroyed by the actions of its creator.

Gustav Metzger: Auto-Destructive Art (1959)

Auto-destructive art is primarily a form of public art for industrial societies.

Self-destructive painting, sculpture and construction is a total unity of idea, site, form, colour, method, and timing of the disintegrative process.

Auto-destructive art can be created with natural forces, traditional art techniques and technological techniques.

The amplified sound of the auto-destructive process can be an element of the total conception.

The artist may collaborate with scientists, engineers.

Self-destructive art can be machine produced and factory assembled.

Auto-destructive paintings, sculptures and constructions have a life time varying from a few moments to twenty years. When the disintegrative process is complete the work is to be removed from the site and scrapped.

Continue reading →