The strange world of childhood is central to Nicky Hoberman’s painting. Like those in Loretta Lux’s photographs, there is something not quite right about these children and the space they inhabit. Here though the children are isolated completely from the context of the world outside and shown against plain coloured backgrounds that offer no clue as to their situation. Though the facial features in Spectre are only slightly out of proportion – there is something especially disturbing about the eye that should be furthest from us being larger than the one we’re closer to – it’s the relationship of the girl’s head to her body that confuses me more. The body – smaller than it should be – lacks detail to the extent that I can’t quite decide whether her head’s even facing the right way.

Tag Archives: painting

Sign systems

Bob and Roberta Smith, Make Art Not War, 1997

Bob and Roberta Smith, Make Art Not War, 1997

There is of course a very long tradition of text painting. It’s just that it’s not an art tradition but a commercial one: signwriting. Though shop signs are seldom painted now it’s still a form we recognise. This is an approach to painting that is about immediate communication of a message. And it’s an approach Bob and Roberta Smith uses very effectively as art.

Hiding in plain sight

Sean Landers, Navel Gaze, 1995

If a picture paints a thousand words then what happens when the picture is words? Sean Landers uses painting as a way to tell stories but it’s not the picture part of the equation – when there is one, and more often than not there isn’t – that does the talking. It’s all those words.

I saw Landers’s work first in Young Americans at the Saatchi Gallery in, I think*, 1996. I remember being mesmerised by it. I made a very good attempt at reading the paintings but I think I failed. By the time you’re about three or four lines in it’s hard to get from the end of one line to the start of the next without skipping or re-reading so hoolding on to the thread of the narrative becomes troublesome.

It’s only words

John Baldessari, Everything is Purged from this Painting, 1968

John Baldessari, Everything is Purged from this Painting, 1968

Thinking about books becoming art yesterday made me ponder the use of text – one of the raw materials of books – as art. Language is key to the conceptual art of the 1960s, with the idea taking precedence over aesthetics. Inevitably the resulting work could be rather dry and hard to engage with, but this is far from universally true. John Baldessari’s text paintings work on several levels for me. Firstly, Baldessari confuses matters by rendering his text in paint on canvas. Secondly, the text is often funny, especially in the context of painting.

Through the trees

Peter Doig, Concrete Cabin, 1994

Peter Doig, Concrete Cabin, 1994

Thinking about houses in the middle of nowhere for the previous post started me thinking about a couple of Peter Doig paintings and in particular what gives them a very different feeling to Michael Raedecker’s landscapes. The most obvious difference is in the time of day depicted; these are daytime scenes which makes for a very different feel. And they’re straightforward paintings, whereas part of the strangeness in Raedecker’s scenes comes from the use of stitch in the paintings. But, of course, it’s more than that.

After dark

Michael Raedecker, Ins and Outs, 2000

Michael Raedecker, Ins and Outs, 2000

There’s something about houses in the middle of nowhere. In some respects I can see the attraction of living in a modernist box surrounded by trees, although clearly in practice I’d miss the tube and being able to get to galleries and theatres and the cinema and decent shops and, oh, the list goes on but it gets too boring to type. In the end though, surprisingly, it’s not fear of not being in London that’s the biggest factor, it’s the fear of just not knowing what’s out there. Okay, so being in a hermetically sealed glass box might be warm and safe but if you can’t see what’s outside, well, it could be anything.

Animal stories

Paula Rego, Pregnant Rabbit Telling Her Parents, 1982

Paula Rego, Pregnant Rabbit Telling Her Parents, 1982

As the cliché has it, a picture paints a thousand words. I’m not sure how often that’s actually true – if ever – but Paula Rego certainly gives it a good go. There is frequently a personal element to the stories she tells though for me the pleasure more often comes from setting the background aside and letting the image do the talking. Casting animals in the roles of her protagonists mean that Rego’s stories often make me smile. In this respect a particular favourite is Pregnant Rabbit Telling Her Parents. Actual rabbits of course must spend a good deal of time pregnant, so their parents would be unsurprised by the news the painting’s title character is breaking – indeed Rabbit has a somewhat brazen, what of it look about her – but actual rabbits would also have rabbits as parents. In the world of Paula Rego that would be far too easy.

Glossy indifference

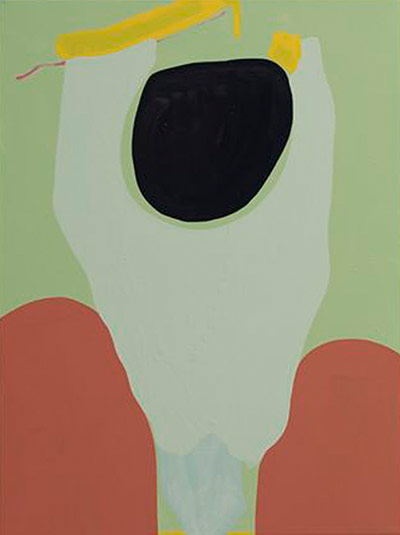

Gary Hume’s exhibition The Indifferent Owl is as slick and polished as one might expect from an artist who paints with gloss paint and exhibits at White Cube, but for me, though I generally like Hume’s work a lot, there is something missing. Quite what that something is I don’t know but maybe it’s the indifference in the exhibition’s title seeping out and affecting the way I see the work.

Size isn’t everything

Anselm Kiefer, Dat rosa miel apibus, 2010-11

Anselm Kiefer, Dat rosa miel apibus, 2010-11

There is something extraordinary about Anselm Kiefer’s paintings. The surfaces aren’t quite like anyone else’s and the scale of the work means that standing before one I always feel part of the picture space. The paintings in Kiefer’s exhibition Il Mistero delle Cattedrali at White Cube Bermondsey are less heavily textured than some of his work but the surfaces are still rough and often salty.

Moving pictures

Juan Fontanive, Quicknesse, 2009

Juan Fontanive, Quicknesse, 2009

When we think of moving image art it’s usually film and video works that spring to mind first, but artists like to play and there’s more than one way to make an image move. One of the works I’ve enjoyed the most in recent years is Juan Fontanive’s Quicknesse, a simple flipbook device which traps a hummingbird in a loop of hovering. The sound of the work conjures a sense of agitation and urgency; the bird is beautiful, trapped in our gaze.

There is something extraordinary about this work. Whether it’s the simplicity of the device or the touching beauty of the image, in which the bird is isolated from its surroundings (the background of the image is painted out in white so that the bird floats), I’m not sure, but it has stayed with me since the first time I saw it. Effectively this is stop motion animation as sculpture. Juan Fontanive has another London show opening at Riflemaker Gallery next month. Can’t wait.