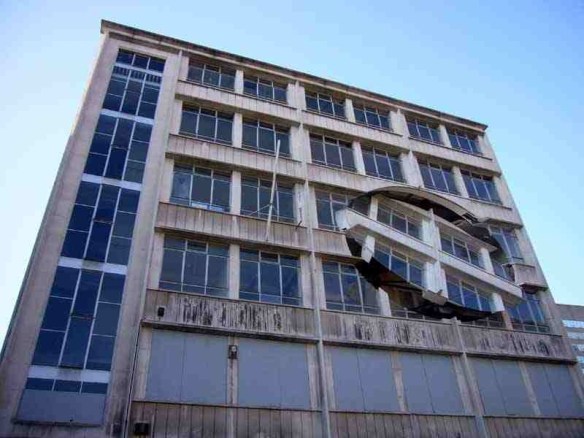

Richard Wilson, Turning the Place Over, 2007

Quite high on the list of art I wish I’d seen is Richard Wilson’s installation for the 2007 Liverpool Biennial. Like other works by Wilson, who is probably best known for his installation 20:50 at the Saatchi Gallery (about which more another time, possibly even tomorrow now that it’s in my head), Turning the Place Over was an architectural intervention on an ambitious scale but unlike 20:50 this was a temporary installation made by messing with the fabric of an empty building.