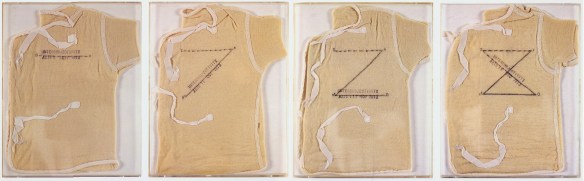

Sally Mann, The New Mothers, 1989

Sally Mann, The New Mothers, 1989

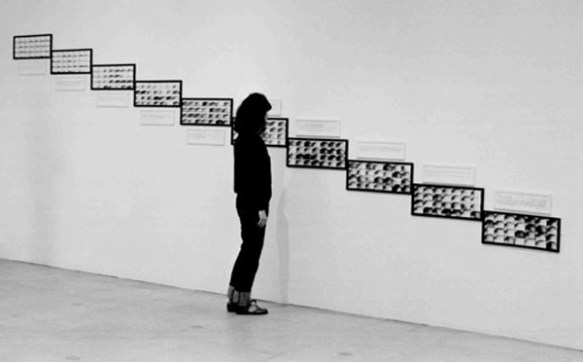

Sally Mann’s series of photographs of her children Emmett, Jessie and Virginia, made over a seven year period and both exhibited and published as Immediate Family, tells of the freedom of long hot summers spent in the countryside around the family’s home in Lexington, Virginia. Mann photographed the children only in the summer when they were out of school and free to play. Made with a large format camera, the pictures are very far removed from the informal snapshots we generally take to document family life. These pictures – whether they look it or not – are deliberately posed and carefully made. The children are playing but their play is for the camera.

Given the heat of the Virginia summer, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the children are often naked and it’s this that has caused the greatest controversy. Given the hysteria that now surrounds images of children it’s hard to see Immediate Family without factoring in the issues that now surround the representation of children.